[00:00:00] Section: Podcast introduction

[00:00:00] Anna Stoecklein: Welcome to Season 3 of The Story of Woman. I'm your host, Anna Stoecklein.

[00:00:05] Anna Stoecklein: From the intricacies of the economy and healthcare to the nuances of workplace bias and gender roles, each episode of this season features interviews with thought leaders who provide fresh perspectives on critical global issues, all through the female gaze.

[00:00:20] Anna Stoecklein: But this podcast isn't just about women's stories. It's about rewriting our collective story to be more inclusive, equitable, and effective in driving change. It's about changing the current story of mankind to the much more complete story of humankind.

[00:00:42] Section: Episode level introduction

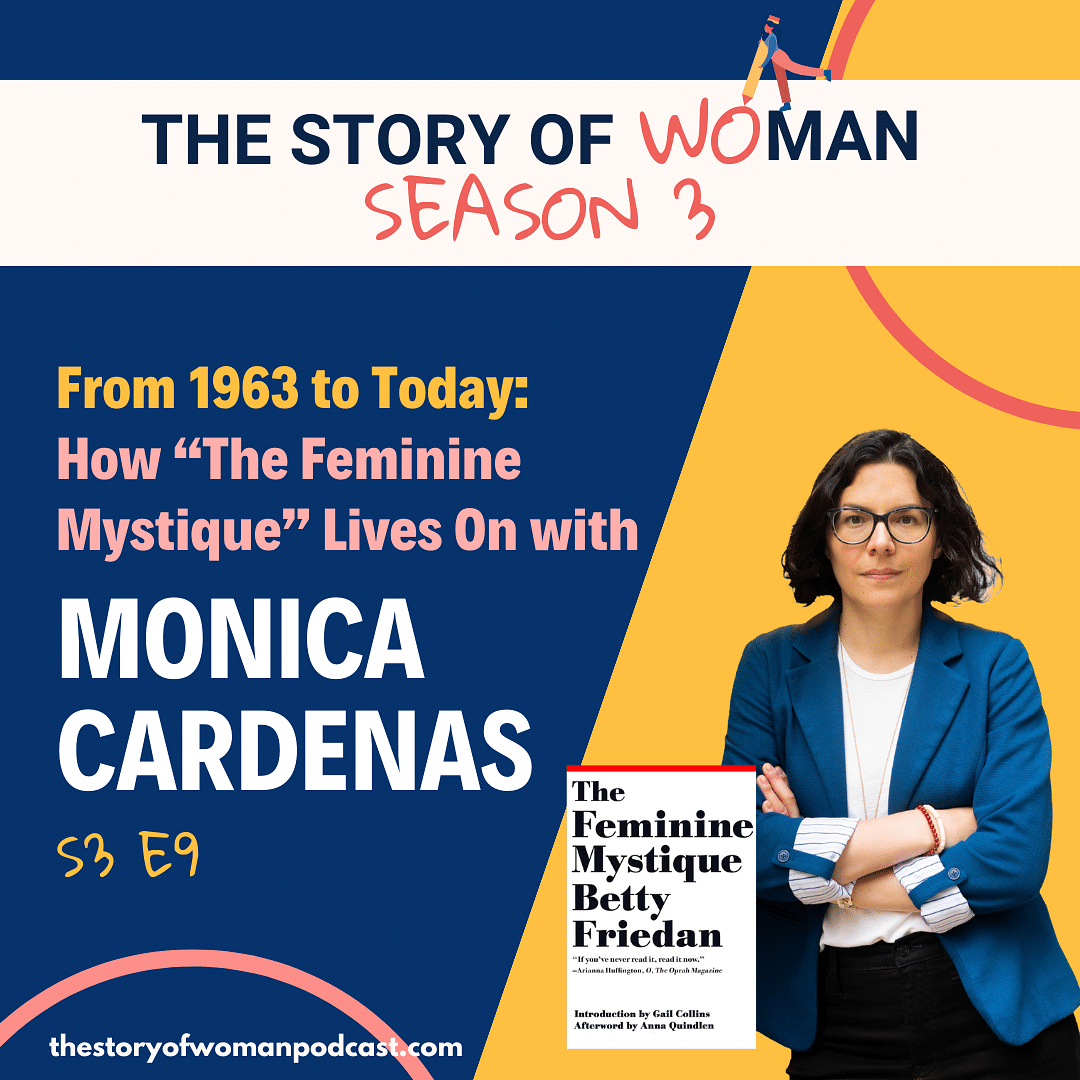

[00:00:44] Anna Stoecklein: Hello and welcome back to another episode of The Story of Woman. In this episode, I speak with Monica Cardenas about the book that's been widely credited with sparking the second wave of feminism in the United States, The Feminine Mystique by Betty [00:01:00] Friedan.

[00:01:00] Anna Stoecklein: Even though this book was published in 1963, I really wanted to include it in the podcast because there are just so many parallels to the issues we're still facing today: the domestic and maternal expectations placed on women, the shame and blame that happens when women step outside of that role or maybe do it a little bit differently, the cultural and legal barriers that limit our reproductive choices, the way all of these barriers disproportionately impact women of color and other marginalized groups and so much more that was talked about and raised, and an issue back then that we're still seeing today, just with a slightly different color coat on.

[00:01:42] Anna Stoecklein: Uh, so I, really wanted to talk to Monica about all of these parallels, really looking at what The Feminine Mystique was in 1963, how much progress has been made since then and exploring this idea of a "motherhood mandate", which is a phrase that was used by [00:02:00] psychologist Nancy Felipe Russo in 1976.

[00:02:04] Anna Stoecklein: And then in the second half of the episode, we really explore what the modern day version of The Feminine Mystique is. We also talk about the importance of literature in shaping our culture and what books like this do for the feminist movement and for driving progress.

[00:02:19] Anna Stoecklein: I'll have Monica introduce herself in the beginning, so I'm just going to jump right into the conversation, but you may recognize her voice as this is the same Monica Cardenas that was a guest host for episode three of this season, the conversation with Chelsea Connaboy about her book, Mother Brain. So if you haven't listened to that episode yet, be sure to check it out.

[00:02:40] Anna Stoecklein: And as always, if you like what you hear, please take a minute to rate and review, share with a friend, or consider becoming a patron of the podcast for access to ad free listening and bonus content, which there is some for this episode that didn't make it into the final cut. But for now, please enjoy my [00:03:00] conversation with Monica Cardenas.

[00:03:02] Section: Episode interview

[00:03:03] Anna Stoecklein: Hi Monica. Welcome and thanks so much for being here with me today.

[00:03:08] Monica Cardenas: Thank you for inviting me.

[00:03:10] Anna Stoecklein: Absolutely. I'm really excited for this conversation today because you know it's a little bit different than the standard ones because we're talking about a book that was written in the fifties and wasn't written by yourself, as opposed to some, a lot of the previous conversations that I've had. We're talking today about The Feminine Mystique, and specifically we'll be looking at how that has, uh, kind of what is the modern day feminine mystique today?

[00:03:39] Anna Stoecklein: And that's where you and your work come into play. So before we get into the book and all of the wonderful things and not so wonderful things that we are going to talk about, I'd love to just have you introduce yourself to us and, what you focus on in your work and how that ties into what we're gonna be chatting about.

[00:03:59] Monica Cardenas: [00:04:00] Sure, sure. I'm Monica Cardenas. I completed my PhD in English and Creative Writing at Royal Holloway University of London last year, and my research is about the representation of non maternal women in literature. And how misguided perceptions of womanhood and femininity can limit reproductive freedom.

[00:04:22] Monica Cardenas: So as part of that, I reviewed particular US Supreme Court decisions that relate to reproductive rights, as well as selected novels that feature protagonists in some way wrestling with fertility rights. And alongside that, I wrote my own novel that features a heroine in a similar position, but with some political intrigue and current abortion rights topics mixed in. But I'm still waiting for the an agent or publishing opportunity to come through on that.

[00:04:52] Anna Stoecklein: So if anybody's out there, holler.

[00:04:54] Monica Cardenas: Yes, please.

[00:04:56] Anna Stoecklein: So, as [00:05:00] mentioned today, we are talking about the Feminine Mystique, which was a book by Betty Friedan that was written in oh, 1963, I lied, not the fifties, but 1963. And it's widely credited with sparking the second wave of feminism. And today we'll be really looking at how far we've come, in terms of women's role in society, and specifically women's maternal and domestic role. And that's what the Feminine Mystique is about. That's what your work centers around.

[00:05:29] Anna Stoecklein: And I wanna give a caveat in the very beginning, and we'll talk about this throughout, that as influential as this book was, it has lots of problems with it. The main one being that it focused solely on a problem that was experienced mainly by white, straight, middle class women. And like I said, we'll, we'll get into all of that today, but I just think it's worth mentioning upfront. And that despite these flaws, I do still think it's worth looking at. And we'll be [00:06:00] looking at it specifically in the reproductive rights context and drawing out parallels between this moment when the book was written just before the second wave of feminism and the current moment that we're in now.

[00:06:13] Anna Stoecklein: So to start, let's talk about what the feminine mystique even was. So Monica, can you tell us about the book and what was this feminine mystique?

[00:06:24] Monica Cardenas: Right. You said the book was published in 1963. But I think you were right about it being sort of based on what was happening in the forties and fifties. And it's something that Friedan, you know, only was able to publish in the sixties, but she says the feminine mystique is basically the belief that women are most fulfilled by being feminine, by being a housewife, a dotting mother and wife who stays in the home and keeps it nice and cooks and cleans all day.

[00:06:58] Monica Cardenas: So it was that sort of [00:07:00] idea that was perpetuated through magazines and the culture after the war that she was interested in and how it affected her contemporaries at that time.

[00:07:12] Anna Stoecklein: Yeah. And to bring this to light even more, I just wanna read the first two paragraphs of the book. And it's really referred to a lot as "the problem that has no name" because it's like this mysterious thing that women experience and we just don't know what it is, why they're so unhappy in these roles when they have everything that they need.

[00:07:34] Anna Stoecklein: You know, they're living out this, this American dream. I mean, cuz this book also that caveat was really centered around American women specifically. But yeah, so, so this is the first two paragraphs of the book.

[00:07:47] Anna Stoecklein: So "the problem lay, buried, unspoken for many years in the minds of American women, it was a strange stirring, a sense of dissatisfaction, a yearning that women suffered in the middle of the 20th century in the [00:08:00] United States. Each suburban wife struggled with it alone as she made the beds, shopped for groceries, matched slip cover material, ate peanut butter sandwiches with her children, chauffeured cub scouts and brownies lay beside her husband at night. She was afraid to even ask herself the silent question, is this all? For over 15 years..."

[00:08:20] Anna Stoecklein: Cause that's kind of like you said, the, the period before this book was written is kind of the period where all of this was really building up after the war. So...

[00:08:28] Anna Stoecklein: " For 15 years, there was no word of this yearning in the millions of words written about women, for women, in all the columns, books and articles by experts telling women their role was to seek fulfillment as wives and mothers.

[00:08:40] Anna Stoecklein: Over and over, women heard in voices of tradition and Freudian sophistication that they could desire no greater destiny than to glory in their own femininity. Experts told them how to catch a man and keep him, how to breastfeed children and handle their toilet training. How to cope with sibling rivalry. How to buy a dishwasher, [00:09:00] bake bread. How to dress, look and act more feminine. How to keep their husbands from dying young and their sons from growing into delinquents. They were taught to pity the neurotic unfeminine, unhappy women who wanted to be poets, physicists or presidents.

[00:09:16] Anna Stoecklein: They learned that truly feminine women do not want careers, higher education or political rights, the independence and opportunities that the old-fashioned feminist fought for. Some women and their forties and fifties still remembered painfully giving up those dreams, but most of the younger women no longer even thought about them. A thousand expert voices applauded their femininity, their adjustment, their new maturity. All they had to do was devote their lives from earliest girlhood to finding husband and bearing children."

[00:09:49] Anna Stoecklein: So yeah, that really, I mean, I think we can all, we can all imagine that pretty well, and I think we can also already start to hear the parallels between what was going on [00:10:00] then and today.

[00:10:01] Monica Cardenas: For sure. Yeah. There is a parallel today actually. There's the tradwife hashtag trending on social media that sort of hearkens back to all of what you just read, that whole lifestyle. And that hashtag is used by women who embrace that kind of lifestyle and talk about all the joy that it brings them.

[00:10:27] Anna Stoecklein: Of being a housewife? or, I see.

[00:10:31] Monica Cardenas: Care of by their husband, financially speaking, and, just being in the home and not aspiring to more than that. But that trend is sort of, I think, overshadowed by the problems we're facing now in the US with reproductive rights being pushed back even more. So I think the parallels are maybe more than coincidental, but we get into that later.

[00:10:57] Anna Stoecklein: Mm-hmm. Definitely. [00:11:00] Interesting. I haven't heard of that hashtag. And of course, you know, and we'll get into people who want to be mothers and fulfillment, you can get out of this, but it's like, even if this brings fulfillment to some women, this will never bring fulfillment to half a population. You just cannot, um, blanketly apply that to everyone.

[00:11:20] Anna Stoecklein: And something else, one other thing just to say about the feminine mystique from my perspective before I get into my next question with you is, you know, that another big component of this in this time period is that it was starting to become a known problem, like you said in the magazines and, you know, the media, doctors, and counselors and educators, people were talking about it because women were voicing how they were feeling tired and these different components that really stemmed from mental health and wellbeing. And they were giving it names like housewife fatigue and the housewife's blight.

[00:11:54] Anna Stoecklein: But along with this, it was mostly always just dismissed, you know, [00:12:00] saying women should feel lucky for everything that they have or blaming women's education, which of course just naturally made them unhappy in their roles as housewives. Or the classic saying, women need to just have more sex and more children and that, that would solve it. But basically all of the quote unquote solutions were around women themselves and what's wrong with them rather than society and, you know, women's second tier status within it.

[00:12:28] Monica Cardenas: Yeah, Yeah, and those problems, I think all that you outlined, logically, any other person would look at them and think, oh, well, maybe all women aren't happy just being a housewife. But instead, the so-called experts looked at it and thought, well, they just need to get on board with this. Oh, they should be happy. Rather than, you know, seeing those problems for exactly what they were.

[00:12:54] Anna Stoecklein: Yeah, exactly. The focus on the individual. And then of course what that does is [00:13:00] when a woman is feeling these things, she thinks something is wrong with her. She internalizes that, she's not gonna admit her dissatisfaction or she'll feel shame around that. And then she also doesn't know that other women are feeling this way.

[00:13:13] Anna Stoecklein: So it's like in isolation, and again, I think of a parallel with today and after the pandemic, everything that's coming to light with all of the hidden care work and domestic responsibilities and all of the burden and burnout and everything that really has come to light that, you know, a lot of working mothers especially were maybe not understanding or, you know, were kind of in isolation and the pandemic has helped bring that to light. So again, another kind of parallel.

[00:13:42] Monica Cardenas: Yes, I think what we've seen is that of course women have more freedom today than they did in the sixties. It's not strange for a woman, a mother, to have a career outside the home. But we haven't made it any easier for them [00:14:00] to be able to pursue those careers alongside motherhood. So, I think women are just sort of expected to, okay, fine, if you want a career, you can do that, but that doesn't mean that all your other responsibilities go away or that anyone else is gonna help with it or that there'll be any support otherwise. So, it's not really a freedom in that sense, in my opinion.

[00:14:24] Anna Stoecklein: Mm-hmm. Yeah, it's just now you have two jobs.

[00:14:28] Monica Cardenas: Right.

[00:14:30] Anna Stoecklein: Okay. So then looking back to 1963, and Betty, women, before this book was written, before these 15 years, women were still always expected to be in the home. So what was different about this era in particular, do you think, compared to decades in the past?

[00:14:51] Monica Cardenas: Yeah, I think, the big thing obviously was World War II when all of the men were fighting women filled more [00:15:00] employment roles. They started pursuing, higher education. And then when the men returned, the women were expected to sort of fall back and open those spaces up for men again.

[00:15:12] Monica Cardenas: And of course to build up the population, the mystique was perpetuated that women would be happiest, even college educated women, you know, who were ostensibly, interested in a career, would be happier at home with their husband raising kids. And I think for me, that that image is most familiar in the British phrase that was popular after the war, "Lie back and think of England", make babies...

[00:15:42] Anna Stoecklein: Uh, lie back and think of England. I haven't heard of that. Wow.

[00:15:46] Monica Cardenas: Something along those lines.

[00:15:47] Anna Stoecklein: Wow.

[00:15:48] Monica Cardenas: I think, you know, the war really brought this drastic shift to light. And that's what, for the timeframe that Fredan is looking at here, but she's looking at women's [00:16:00] magazines and the shift in tone and theme that she sees in that timeframe.

[00:16:06] Anna Stoecklein: Mm. Yeah. And you know, she writes about the statistics as well in the book that the average marriage age of women dropped during this time period. The average number of kids rose, the proportion of women attending college dropped. You know, you see this reflected in all the statistics, and I think another big component of it was the kind of materialism and consumerism that came along with this era, right?

[00:16:30] Anna Stoecklein: All of the, the things that you needed to be a good housewife. Can you kind of explain that part a little bit and how you think that played a part in this specific time period?

[00:16:41] Monica Cardenas: Yeah, it was well, I think the, the addition of the Feminine Mystique that I have has an introduction by Lionel Shriver. And she starts by speaking about Mad Men, the television series. And I think that's a really excellent way to frame the Feminine Mystique. If [00:17:00] you're familiar with it, because of course, the main character Don works at an advertising agency and he has this 1950s beautiful housewife Betty, who also was suffering from some mental illness because I think she unhappy with the, you know, her absent husband, philandering husband, and was kind of stuck in the suburbs all day.

[00:17:24] Monica Cardenas: And she used to have this cosmopolitan life. So it's kind of exactly what Fredan is talking about with the element of the consumerism. In Mad Men we see Don selling products mostly to women who are at home watching television during the day or flipping through magazines. So having all that stuff to be a good, quote unquote good housewife, became really important.

[00:17:51] Monica Cardenas: And selling it became a big deal too. I think it became a huge part of the economy. And of course, I mean, we [00:18:00] see the same thing today, probably not just aimed at wives and mothers, but consumerism is such a huge part of our economy. And the declining birth rate that we have today plays a part in that conversation still.

[00:18:16] Monica Cardenas: Making sure we have enough people to, you know, fill these jobs and support an older population and buy stuff. It's an important issue related to the economy, according to some experts. So yes, I think having all that stuff as a housewife was a big part of it. It filled magazines, and I think, In Against White Feminism, which was published two years ago by Rafia Zakaria, she talks about how consumerism played a part in feminism and how it was related to femininity. And I think she gives a really great example, I think she says, because there were dozens of laundry detergents that a housewife needed to choose between, she was sort of distracted from the movement [00:19:00] and from freedoms because there were all these choices to make around making the perfect home and being the perfect wife and mother.

[00:19:10] Anna Stoecklein: Mm, yeah. And then the guilt on top as well of, well look at all of these, you know, the washing machine, the dishwasher, these things that make your job so easy. So you should be thankful and, you know, excited for all of these new products that are...

[00:19:25] Monica Cardenas: Yes, exactly. And I think...

[00:19:28] Anna Stoecklein: you're welcome.

[00:19:29] Monica Cardenas: ...that was part of the whole narrative. The story was not that women were less important than men because men had these important jobs, they went out of the house to do. It was that women's jobs were as important or maybe more important because they were supporting the husband and keeping the home running, and they needed all of these things in order to do that very important job.

[00:19:54] Anna Stoecklein: Mm-hmm. Yes. So then how did all of this feed into [00:20:00] women's reproductive freedoms back then?

[00:20:04] Monica Cardenas: Well Friedan doesn't talk directly about, not at length, at least about reproductive freedoms, but of course the choice to have a child is tied up in resisting this narrative of that being the only thing a woman can do. And she shares one story of a woman she interviewed who just says, the woman, says sort of flippantly at one point that she's jealous of her neighbor. And Friedan assumes that she's joking because the neighbor has a busy, high-powered career. But the mother says, no, actually I wasn't joking. I am jealous of her because she knows what she wants and I don't know what that is. And the only time I feel I have any important role is when I have a baby. And I can't just keep having babies. You know, babies grow up and they do their [00:21:00] own thing.

[00:21:00] Monica Cardenas: So that's one of the ways I think it ties into reproductive rights is if a woman wants to feel important or empowered, the only way she felt that at this time was to have a child. And if that's not something that you want for yourself, then that really hinders your rights.

[00:21:20] Monica Cardenas: And of course, at this time, I should say it wasn't until 1965, embarrassingly, so two years after the Feminine Mystique came out, 1965 Griswold versus Connecticut, the Supreme Court decided that there was a right to what they called marital privacy against state restrictions on contraception. So essentially they said married couples were legally permitted to use birth control in 1965, and then that was extended to unmarried women in 1972.

[00:21:55] Monica Cardenas: So technically speaking, it was not legal to use contraception [00:22:00] until those decisions. So of course that severely limits your reproductive rights if there's no legal access to contraception.

[00:22:08] Anna Stoecklein: Mm-hmm. Yeah. So there's like the cultural influence on reproductive freedoms, the lack of choice there, and then the actual medical and legal restrictions on reproductive freedoms.

[00:22:21] Monica Cardenas: Right. And then we had Roe in 1973 that made abortion legal. And then of course, as everyone knows last year, that was rolled back severely.

[00:22:33] Anna Stoecklein: Mm-hmm. Yes. And we'll get into, we'll get into to the today's, but I wanna have you talk to what we mentioned in the beginning, which was how marginalized groups were left out. So can you kind of elaborate on that point for us, and how marginalized groups were impacted by this feminine mystique narrative back then?

[00:22:54] Monica Cardenas: Yeah. I think, if you read the Feminine Mystique on its own, you might think that all [00:23:00] women in the sixties were white, middle class moms, wives and mothers. But of course there were still single mothers, obviously there were women of color who had, maybe were in the same circumstances as these women or were lower income, married or single, and any working class person, of course, is not facing the same problems that the, the women in the feminine mystique were facing.

[00:23:31] Monica Cardenas: They maybe would've been thrilled to have the opportunity to be home with their kids and see them if they were also working at the same time and struggling to do both things. So to an extent it probably read to those groups and even today as You know, oh, it doesn't sound so awful to a lot of people to be able to be a one income household and devote yourself to your kids. I'm sure lots of mothers would love [00:24:00] that opportunity, but can't do it financially. So, I think that was a major lack of this book is it didn't consider those demographics.

[00:24:10] Anna Stoecklein: Yeah, yeah, they were erased and because of that, when you think about the fact that it didn't consider this, you know, almost the majority because when you look at all the different marginalized groups, cuz he even likes when sexual orientation, and people who aren't in heterosexual relationships working class, yeah, it's disproportionately women of color who have always been working outside of the home, out of economic necessity. Exactly as you say, that when they're excluded and then you think about the fact that this book really helped kickstart the second wave of feminism, you can really start to see and understand how we're still dealing with white feminism, which was so firmly embedded in that wave and the decades to come. And then you give rise to books like Against White Feminism. I've had Koa Beck on the podcast with her book White Feminism that looks [00:25:00] at all of the ways that marginalized groups continue to be left out of the more mainstream feminist movement. And yeah, you can really see when something as influential as this kickstarts that, how that's gonna have ripple effects.

[00:25:17] Monica Cardenas: Yeah. I think that at this time, and I'm sure today to a large extent, there's a tendency to exclude other groups maybe under the misguided belief that you can be more effective if you just like, hone in on one problem. And Friedan was criticized for that. I mean, during the second wave feminism, I think she advocated for leaving out homosexuals so of out of the movement.

[00:25:48] Monica Cardenas: So I think that it lost stamina. And we see now that inclusivity, of course, like the more voices saying the same thing, the better. And [00:26:00] that's something that, Rafia Zakaria mentions in against white feminism. And I'm sure you see the same thing in White Feminism.

[00:26:07] Monica Cardenas: So, I think we can also see a similarity with Margaret Sanger who helped develop the birth control pill. She was later criticized for embracing the eugenics movement, which I've always been interested in, you know, wanted to know if that was by what she believed to be a necessity to get more people behind her effort to develop the birth control pill with, you know, the understanding that as long as the pill is out there, who does it hurt?

[00:26:40] Monica Cardenas: But of course, a lot of people got hurt in the development of the pill. So I think we see the same kind of struggle repeating throughout and we need to just embrace the inclusivity and make sure that everyone has a voice.

[00:26:56] Anna Stoecklein: Mm-hmm. Absolutely. And then just to read this [00:27:00] one line that I found from this feminist thinker, this woman Kelly Elaine Navies. She said, "In retrospect, as a catalyst for the second wave of feminism, The Feminist Mystique was a factor in the evolution of Black feminism. And that Black feminists were compelled to respond to the analysis it lacked and develop a theory and praxis of their own, which confronted issues of race, class, and gender."

[00:27:26] Anna Stoecklein: So in addition to the lack of the kind of more mainstream, you also see an evolution in a building of intersectional feminism and Black, you know, whatever you wanna call Black feminism or these different ways of thinking that yeah, confront the intersections of gender and other marginalized groups.

[00:27:46] Monica Cardenas: Yes. Yeah.

[00:27:48] Anna Stoecklein: Okay, so one more question on the back then before we get into today, which was, you know, kind of what happened after. So this book comes out, it's really shedding a light on [00:28:00] everything that lots of women in a certain demographic are experiencing. What happens and what types of ideas or progress did this book set in motion?

[00:28:11] Monica Cardenas: As of 2020, it sold over 3 million copies, so obviously it became extremely popular. But at publication, I think a lot of women felt validated for their feelings, but many overwhelmingly felt insulted because it is sort of making a mockery of their lives. Friedan spends a large part of the book explaining how magazines evolved from I guess a more equal content, including interesting literature and fiction and current events, and then into this time period in the fifties writing articles almost exclusively on how to be a good housewife and raise your children, and all those examples you read in the introduction.[00:29:00]

[00:29:00] Monica Cardenas: So that could be read as sort of in infantilizing these women who have embraced this lifestyle. And I think it's important to point out that of course there are plenty of people in the world who would be entirely fulfilled by their family alone and running a household, which is hard work. But the problem identified in The Feminine Mystique is that of course that doesn't apply to every person. And that women need to have options in the same way that men do.

[00:29:34] Anna Stoecklein: Yeah. I feel like it really, really highlighted the societal constructs that were behind all of this, that were harming them. Because like we were saying before, before it was just, well, the woman should be more happy. Or the woman this, the woman that, and this was really looking at the system as a whole, or at least some people within the system.

[00:29:55] Monica Cardenas: Right.

[00:29:55] Anna Stoecklein: As we've said.

[00:29:56] Anna Stoecklein: Okay. So then looking at today, [00:30:00] we all understand this Betty Crocker glorified homemaker era. And a lot of us, you know, might feel like we've moved past that, in, in certain countries in certain demographics. But you know, really the problems have not gone away. We're just in a new kind of era. So what do you think the feminine mystique of today is?

[00:30:24] Monica Cardenas: I think the feminine mystique of today is that women are still expected to want children. And I think any woman of a certain age has experienced that question posed by you know, family strangers. When, when are you gonna have kids? When are you gonna settle down? I think that there's a sort of built in expectation that eventually that is what a woman wants.

[00:30:56] Monica Cardenas: And that in spite of [00:31:00] decades of writing about this topic from various experts, that cultural idea of what a woman wants has never gone away completely. And just last month, Ruby Warrington published a book called Women Without Kids that embraces this idea of not having children. But reading it now, alongside The Feminine Mystique is really frustrating to see how many of the same topics we're still covering rather than having moved past this.

[00:31:38] Anna Stoecklein: Do you have some examples of some of the same topics that we're still covering?

[00:31:43] Monica Cardenas: Well, I think it's just the assumption that women want kids, that every woman wants kids. And I think what Ruby Warrington does really well is talk about all the other things women might want.

[00:31:56] Monica Cardenas: But, um, yeah. [00:32:00] Um, and that, but that's something that we see in The Feminine Mystique as well, is that some women want to be poets or physicists, like you said in the introduction, and we're still talking about how that's a reality rather than just accepting it as a truth.

[00:32:19] Anna Stoecklein: Mm.

[00:32:20] Monica Cardenas: Yeah, I guess that's, that's basically it, is that we we're still having this conversation and I'm tired of having this conversation, but the only way to change it is to keep talking about it and make people understand.

[00:32:35] Monica Cardenas: In Women Without Kids, Ruby Warrington talks about the inclusivity that we were talking about earlier, is that every woman deserves a choice. It doesn't matter what it is, right? It's personal. And I think that is my goal for this part of the wave of feminism, there's a lot in our current wave, but to be able to make that choice and not have to [00:33:00] explain it to anyone. It doesn't have to be because I wanna pursue my career or because I'm not in the right partnership or maybe it's because I don't have enough money, which is perfectly valid and should be addressed in other ways. But just the fact that women don't owe an explanation for the choices they make.

[00:33:23] Anna Stoecklein: Yes. And let's apply that across the board.

[00:33:26] Monica Cardenas: Yeah. Yeah.

[00:33:29] Anna Stoecklein: So any other parallels from the feminine mystique that you wanna point out? You know, we talked about like capitalism and consumerism and the things needed to be a housewife. Do we see those same things with motherhood? And we also talked about that kind of broader conspiracy of the government needing babies after the war. Do we see any kind of broader picture of why we're still having these conversations today?

[00:33:58] Monica Cardenas: Well, I [00:34:00] don't wanna say for certain it's a conspiracy, but..

[00:34:03] Anna Stoecklein: Maybe that's not the right word, but yeah.

[00:34:06] Monica Cardenas: It looks that way. I think it is suspect that at the same time everyone is freaking out about a declining birth rate and the impact it's going to have on the economy that we're also seeing our reproductive rates severely restricted. I mean, in some cases, the restrictions across the United States are, they're just disgusting the way that women are treated as if they can't make their own decisions about their bodies.

[00:34:41] Monica Cardenas: And the complications that working moms face or mothers in lower income brackets face trying to take care of their children with no support from the government, I think just really transparently shows the [00:35:00] cruelty behind the abortion restrictions, right? It's not about protecting the lives of children.

[00:35:09] Monica Cardenas: It's about restricting women's rights and forcing them to have children they don't want or can't take care of. It's about making it out as if women can't make those decisions for themselves, that they need some intervention to make correct decisions.

[00:35:27] Anna Stoecklein: Mm-hmm. Yeah. Again, just like back then, you have the cultural pressures and the medical and legal, and today it's the cultural pressures to be a mom, to have to explain yourself if you don't wanna be a mom, but then also the medical and legal that we're gonna make it very difficult for you to not become a mom. And when you do become one, we're gonna make it even more difficult for you to, to just be one. Um,

[00:35:56] Monica Cardenas: Yeah, and I think for the cultural [00:36:00] aspect is really important because if we are operating under this belief system that all women want to be mothers and critically, you know, this belief that we just inherently know how to do it which has been debunked. And there's a new book out by Chelsea Conaboy called Mother Brain that goes into this, taking care of a baby is a learned behavior. It's not something that people just know how to do. And I think that operating under this assumption that women just know how to do it and they naturally want this, makes it that much harder for moms that are trying to do everything now because number one, they feel like a failure because they don't just automatically know how to do it. And I think support is needed, right? Government support, daycare funding, school funding, child tax credits, all of those things that help [00:37:00] children thrive and help relieve the burden on parents are needed. And I think the conversations around those things don't happen. As long as we think like moms just know how to do it, they'll be fine.

[00:37:14] Anna Stoecklein: Hmm. Again, I'm hearing parallels of the blame, the responsibility, whatever you wanna call it, being on the individual woman. And that will in turn be internalized and think that, you know, if I don't wanna be a mother or if I'm struggling, then that's my own fault, that's my own problem, rather than looking at society as a whole.

[00:37:37] Anna Stoecklein: And obviously these are conversations that we're all starting to have more and more and more, especially with the pandemic, but it's still very far away from being common knowledge or from being accepted by...

[00:37:51] Monica Cardenas: Right. We see, I mean, every day I see a headline that implies that there's something wrong with people who [00:38:00] don't want children. The one that sticks in my head was from a few years ago, and it was something like millennials just want fur babies rather than real babies. And I thought, why do they need to want something other than a child?

[00:38:19] Monica Cardenas: Like there doesn't need to be something else. It might just be a personal preference.

[00:38:25] Anna Stoecklein: It just seems like The Feminine Mystique is, is the same. It's like before it was, you will not be happy and fulfilled unless you are married with kids and living in a house in the suburbs. And now it's like you will not be happy and fulfilled unless you are married and with kids and also having a full-time job. Like, and, and you can live in maybe somewhere beyond the suburbs now, like that's shifted a little bit, but it's like the same, right?

[00:38:53] Monica Cardenas: Yeah, and I think, I mean, all moms will say this, and I should say I'm not, I don't have children, I'm not speaking from personal [00:39:00] experience, but I think you see over and over again, moms, they're criticized if they don't have a job because what what are they doing with their time? Right? Or they're criticized if they do have a job because that's taking their focus off of their kids and it's like they can't catch a break.

[00:39:19] Anna Stoecklein: Mm-hmm.

[00:39:19] Monica Cardenas: So I think we have that problem that stems from this belief in the natural instincts of women wanting to be mothers, alongside women who don't want kids who are constantly confronted with this idea that there's something wrong with them.

[00:39:38] Anna Stoecklein: Yeah. That's something I wanna ask, and that kind of ties into what you've just said is how does this impact women who want to have kids, who want to be a mom, you know, is there a negative impact for them as well?

[00:39:53] Monica Cardenas: Yeah, I think absolutely that's what the point I was making before is that as long as we [00:40:00] operate culturally, governmentally under this assumption that women just naturally want kids and know what to do with a baby, then it's dangerous for everyone because women who don't want kids might be forced by restrictions to abortion rates. And women who do want kids aren't therefore getting the support that they need to do it. Like I said, with government programs, proper healthcare, and particularly with women of color, the maternal mortality rate is horrific, especially for an advanced country like the United States. So without paying proper attention to those things, everyone is hurt by this misguided belief.

[00:40:46] Anna Stoecklein: Mm-hmm. Yeah, so, so talk more about marginalized groups. So we've said in The Feminine Mystique, they were erased and we saw the implications and what happened with that and the rise of white feminism and everything [00:41:00] else. So what about today's version? How does today's version impact marginalized groups?

[00:41:06] Monica Cardenas: Well, we see impacts on marginalized groups because, for example, with healthcare in the United States if you don't have healthcare through your employer, it's really hard and really expensive. I mean, I think Obamacare helped with that, but that hurts women who are seeking abortion care or maternal care, right?

[00:41:27] Monica Cardenas: We see in the Hyde amendment, for example, that took government funds away from abortion care, which just means that people who are reliant on government funded healthcare don't get the care that they want or need. And we see the maternal mortality rate for everyone in the United States as poor, but especially for women of color.

[00:41:52] Monica Cardenas: And I think one of the things that we don't talk enough about especially because of the anti-abortion [00:42:00] movement so loudly tries to paint abortion as a dangerous procedure, is that pregnancy is so much more complicated and potentially dangerous than an abortion.

[00:42:11] Anna Stoecklein: So much more dangerous.

[00:42:12] Monica Cardenas: So many women suffer complications serious illness, threats of death, death. So not having that care in place, especially for lower income women who can't afford to, for example, travel to another state if they live in a state that can't legally give them care anymore because of abortion restrictions their lives are in danger, simply put.

[00:42:38] Anna Stoecklein: Yep. It's absolutely low income women, people of color that are most negatively impacted by all of these abortion restrictions. And the maternal mortality rate for Black women in America is three to five times higher than for white women.

[00:42:55] Anna Stoecklein: And, yeah, when you just look at that and combine with they're the population that is [00:43:00] most forced to have pregnancy, let's say, you know, most impacted by these anti-abortion laws, but also that just means most forced to have pregnancies. And then on top of that, yeah, three to five times more likely to die in America. It's just, it's absolutely abhorrent.

[00:43:17] Monica Cardenas: And I wanna point out that one of the anti-abortion lines on this subject is, I mean, I feel repulsed to just saying it, but they like to say that because more women of color seek abortion care, that by allowing those abortions to take place it is hurting the population of Black Americans.

[00:43:40] Anna Stoecklein: Oh my god.

[00:43:41] Monica Cardenas: Without regard for the fact that the women in question are actively seeking an abortion. They want an abortion. And to imply that their choice is less important than whatever some legislator somewhere in Texas thinks it is,[00:44:00] it's just abhorrent.

[00:44:01] Anna Stoecklein: Mm-hmm. Again, just removing all option of choice and saying we know what's best for you.

[00:44:07] Monica Cardenas: Right?

[00:44:08] Anna Stoecklein: So we've talked a lot about The Feminine Mystique so far, but it's not just The Feminine Mystique, it's all literature that plays an important role in these narratives and, you know, they kind of feed into culture and society and that in turns feeds into the literature we see. But can you tell us about some of other works of fiction and non-fiction that shape the culture and society's expectations of women?

[00:44:34] Monica Cardenas: Yes. My favorite subject. Um, in literary studies, we believe that fiction is quote unquote, consciousness raising. So that's the idea that these novels, while they're not true, can help change the cultural narrative and help people recognize other types of characters, cultures, [00:45:00] places, that kind of thing.

[00:45:01] Monica Cardenas: So I should reference Juliet Mitchell and Alan Sinfield wrote a lot on this subject. And so the books that we see that I think are making a change in how we think about these women. First, in the sixties around the time The Feminine Mystique was published was The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath. That featured a young woman who was afraid of getting pregnant because she wanted to be a poet. And I think that was really radical at the time. But what's interesting to me is that in The Bell Jar, she does have a baby, we know that in the first couple of pages she references the baby and then we go back to this time when she didn't think she wanted to have a child.

[00:45:45] Monica Cardenas: So I think that kind of speaks to the time. But fast forwarding to today, I think a lot of novels I've been reading lately have these themes in place. We had The Mothers by Brit Bennett and An [00:46:00] American Marriage by Tayari Jones, which both treat abortion as sort of a matter of fact thing that happens that doesn't hurt anybody, it's just a thing that happens that sort of changes the dynamic of relationships maybe, but, none of the women that experience the abortions in these books are, you know, traumatized by it in any way, which I think is really important that we see stories where it doesn't ruin your life.

[00:46:29] Monica Cardenas: I mean, statistics show it doesn't for most people it doesn't need to be this dramatic, horrible thing that the anti-abortion movement tries to paint it as. And then in Miko Kami, her work has just been translated into English in the last few years, and it's really great. And her novel, Breasts and Eggs features a character that is single and wants a child and she goes to great lengths to do that. And I think just seeing women in those [00:47:00] different roles, making choices, owning those choices for themselves makes a big difference in how we see the world and how we see women who choose not to have children.

[00:47:11] Anna Stoecklein: Definitely.

[00:47:13] Anna Stoecklein: So where do we go from here? Uh, looking forward, because you know, as we've talked about, on the one hand, huge strides have been made since The Feminine Mystique was published. But on the other hand, no strides have been made because it was published pre-roe. And here we are again in a world without Roe and in a world where our government is still restricting our reproductive rights and society and culture are still very much set on mandating what is best for women and that thing that is best still has to do with her uterus.

[00:47:47] Anna Stoecklein: So what do you think needs to happen to start not just transforming this mystique into another one for the next generation, because I feel like, you know with my skeptical hat on, that's what I feel like, yeah, [00:48:00] we make progress and it's just gonna evolve and then be another mystique with a different color coat on. So how do we get rid of it all together?

[00:48:10] Monica Cardenas: I think we keep talking about it, keep talking about it, keep writing about it. I think just, I hate this word, but normalizing it. Is really important. I think we saw that with gay rights movement and gay marriage achieving those things. Those were really well supported by seeing people on tv, out in the world, in movies, in books who were just like us. Right? Shocking. And I think just doing the same thing with women who don't have children who are non maternal. And, even stories I've seen about women who regret having children and who are admitting that. And I think just hearing those stories and understanding approaching it with an open [00:49:00] mind, easy to say.

[00:49:01] Monica Cardenas: But definitely the stories, play a huge part in changing how we see the world. Also, continuing to speak up for reproductive rights is a huge, huge part of it. And staying involved in that fight. I think once Roe was overturned, we saw a lot of anger and pushback on that. In states where been a vote on abortion rights on the ballot, overwhelmingly it, abortion rights wins. So I think if we just keep putting that forward, the majority will prevail and the majority believes that women deserve a choice.

[00:49:45] Anna Stoecklein: Do you feel hopeful for the future?

[00:49:50] Monica Cardenas: That's, yes, I do. I do. I have to. And while there are legislators in [00:50:00] certain states that are hell bent on rolling back women's rights, I think there are many more of us who will fight those changes and fight to maintain our rights. So I think no one's gonna go quiet on this.

[00:50:15] Monica Cardenas: And, I'm hopeful yes, that our rights will prevail. And, and with abortion rates, as we've talked about, I think those are entirely entwined with the choice not to have children, right? Even if a child-free person never needs to have an abortion is never pregnant, all of those things tie together and, and maintaining that right is an important part of just allowing women the option in life in the same way men do.

[00:50:44] Anna Stoecklein: Absolutely. Speaking of men, that was one last question I wanted to ask was what do we say about men in, in all of this, you know, what do they stand to gain by helping to get rid of this mystique, this motherhood mandate? How does it [00:51:00] impact them?

[00:51:02] Monica Cardenas: I would like to believe that, men appreciate having, I should say in heterosexual relationships, I think that men would appreciate having an equal, right? Having someone that they, It's not another child. Their wife is not another child, it's a partner. And I think that that's what men stand to gain, right?

[00:51:23] Monica Cardenas: And, they also deserve a choice, not over other women's bodies. But I think just having that open conversation with your partner about whether children is something that you both want or not that's something that both parties in a relationship deserve to have. Not the assumption that children will be foisted on them at some point in their relationship.

[00:51:51] Anna Stoecklein: Totally, and that's within the individual family and relationship. Imagine this narrative starts to change in society. Imagine what that could do [00:52:00] for fathers. You know, we start to value fathers in a way that we don't right now. You know, right now, we put all of this, all I I think of my, oh, one of my friends here in London who's a new father, and I'll never forget, he was talking to me about how sad he felt he was looking for, he was so excited, so excited being a new father and was looking for groups to participate in. You know, he wanted to do things, he wanted to meet other parents. And every group that he was finding was for moms specifically. And he is like, I can't find anything for me. And it just, I could, like, he was so sad about it.

[00:52:38] Anna Stoecklein: And, you know, obviously I say to him, well, you know, you're gonna have to start that group now. But, you know, there's so much that men stand to gain, not to mention paternity leave and just being able to spend more time with their children. And there's, there's so much that could be improved for them, which is gonna make a huge impact [00:53:00] for their children, for everyone involved, for society as a whole, if fathers are welcomed into this mix, instead of just putting all of the focus on women.

[00:53:11] Monica Cardenas: And that can't happen as long as we continue perpetuating this idea that women just naturally know. And it's an inherent gift and the father needs to learn and catch up, that's not how it works. Um, course, you know, there's a hormonal element during the pregnancy and just after the birth, but, men and women equally can take care of a child just as well and I think, yeah, the fathers aren't gonna feel equal in that relationship as long as we continue believing that women are somehow more naturally parental.

[00:53:53] Anna Stoecklein: Totally. And you mentioned before like the infantilization of women that, you know, a lot of this comes from, and that's also like [00:54:00] infantilizing men being like that they're not capable of this. Not to mention, you know, giving an excuse, but that's all just founded on bullshit. So just...

[00:54:09] Monica Cardenas: That's the technical term.

[00:54:12] Anna Stoecklein: Yeah, that's, that's, that's the most technical term I can think of right now. If people take one thing away from this conversation with you today, what would you want it to be?

[00:54:26] Monica Cardenas: I think it would be to approach everyone, no matter their reproductive choices, with an accepting attitude, right? So it's not just leaving child-free people alone in their choices, but also to allow dotting mothers to be dotting mothers and not ridicule them for that. And just allow everyone to embrace their reproductive choices as their own without any judgment.

[00:54:55] Anna Stoecklein: Oh, amen. It sounds so simple. Just [00:55:00] let people do what they wanna do.

[00:55:02] Monica Cardenas: Yeah.

[00:55:03] Anna Stoecklein: Uh, lovely. Monica, thank you so much for your time today. It was a pleasure speaking with you. Thank you so much.

[00:55:11] Monica Cardenas: Thank you. It was great to be here.

[00:55:13] Section: Outro

[00:55:13] Anna Stoecklein: Thanks for listening. The Story of Woman is a one woman operation run by me, Anna Stoecklein. So if you enjoy listening and want to help me on this mission of adding woman's perspective to mankind's story, be sure to share with a friend. One mention goes a long way. Hit that subscribe button so you never miss an episode and make sure to rate and review the podcast while you're there.

[00:55:36] Anna Stoecklein: For more content from the episodes and a look behind the scenes, follow The Story of Woman on your social media platforms. And for access to bonus content, ad free listening, or to have your personal message read at the end of every episode, consider becoming a patron of the podcast. Or you can buy me a one time metaphorical coffee. All of this goes directly into production costs and helps [00:56:00] me continue to put out more and better episodes. In exchange, you'll receive my eternal gratitude and a good night's sleep knowing you're helping to finally change the story of mankind to the story of humankind.