[00:00:00] Section: Podcast introduction

[00:00:00] Anna Stoecklein: Welcome to Season 3 of The Story of Woman. I'm your host, Anna Stoecklein.

[00:00:05] Anna Stoecklein: From the intricacies of the economy and healthcare to the nuances of workplace bias and gender roles, each episode of this season features interviews with thought leaders who provide fresh perspectives on critical global issues, all through the female gaze.

[00:00:20] Anna Stoecklein: But this podcast isn't just about women's stories. It's about rewriting our collective story to be more inclusive, equitable, and effective in driving change. It's about changing the current story of mankind to the much more complete story of humankind.

[00:00:37] Section: Episode introduction

[00:00:38] Anna Stoecklein: Hello, hello. Welcome back. And thank you so much for being here. So for today's episode, we've got a guest host taking over. I tried this out last season with producer, writer, and storyteller Asha Daya, who hosted the final two episodes of that season. And I wanted to keep that going because [00:01:00] among several reasons, women monolith, so the more perspectives that we include in womankind's story the better.

[00:01:07] Anna Stoecklein: So I have ideas of continuing to expand the podcast to include the voices of women who know much more than me about certain topics or who come from different backgrounds and lived experiences. So this is kind of the beginning stages of that idea coming to life. As always, please let me know what you think and get in touch if you have any ideas on this or if you'd like to be considered to be a guest host yourself,

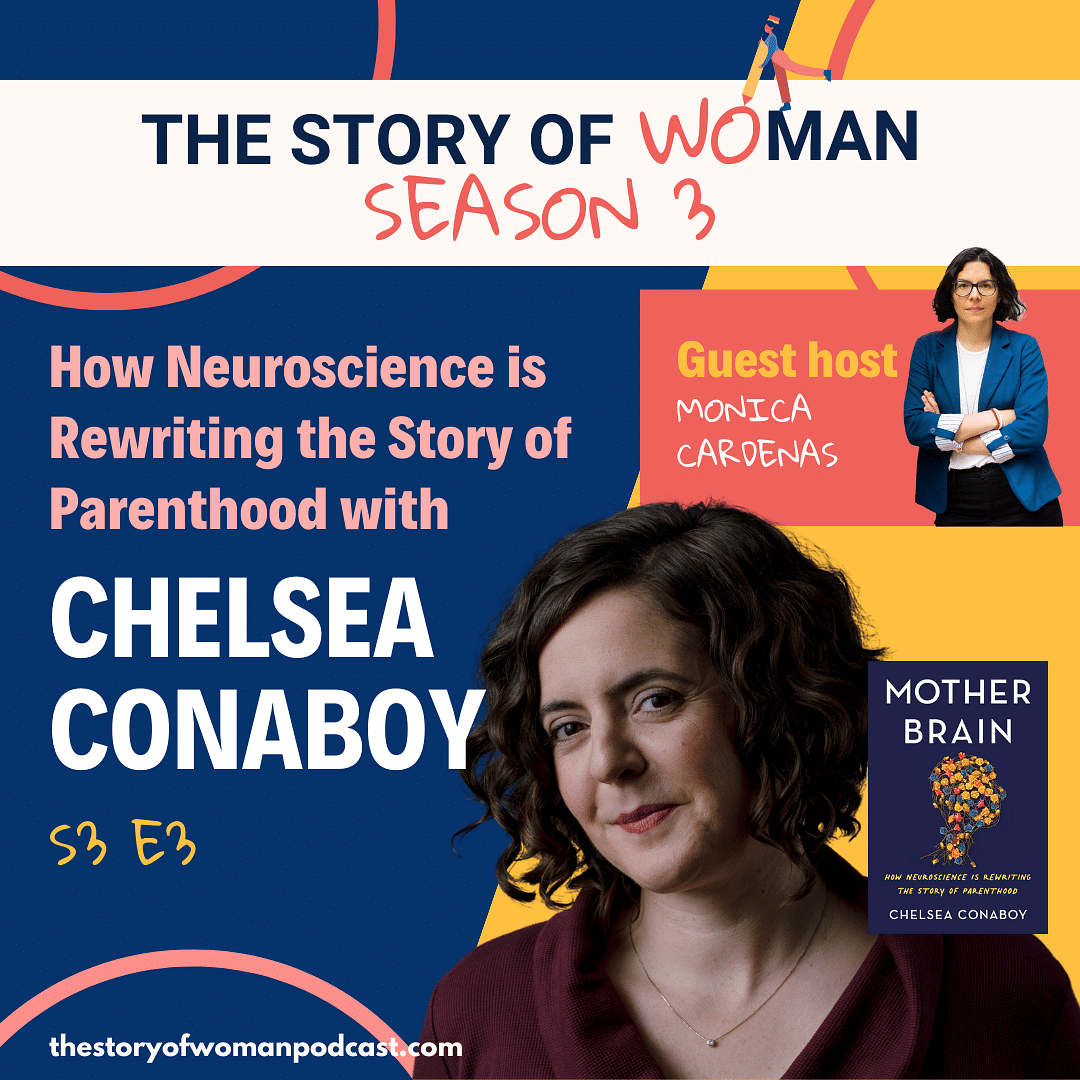

[00:01:31] Anna Stoecklein: Today's guest host is today's guest host is Monica Cardenas. Monica is a London based American writer and scholar. She holds a master's and PhD in English and creative writing from Royal Holloway, University of London. Her research is focused on the non maternal woman in 20th century literature alongside the evolution of reproductive rights in the United States.

[00:01:53] Anna Stoecklein: She's worked as a fiction reader for an online literary magazine and has taught creative writing at the undergraduate and postgraduate [00:02:00] levels. Her work's been featured in a variety of publications and she has a book review blog where she engages with novels featuring non maternal women.

[00:02:09] Anna Stoecklein: And this is why I thought she'd be a great person to speak with Chelsea Connaboy about her book, Mother Brain: How Neuroscience is Rewriting the Story of Parenthood. But I'll let Monica tell you a bit more about Chelsea and what they get into during their conversation.

[00:02:25] Anna Stoecklein: I hope you enjoy!

[00:02:26] Monica Cardenas: Chelsea Conaboy is a health and science journalist based in Maine. Mother Brain , is her first book, published last year and now out in paperback. She's written for the Concord Monitor, Philadelphia Inquirer, Portland Press Herald, and the Boston Globe, part of the team that won the 2014 Pulitzer Prize for coverage of the Boston Marathon bombings.

[00:02:48] Monica Cardenas: Her work has also been published in the New York Times, Mother Jones, Politico, and many other publications. It was such a pleasure to speak to Chelsea about how parents and mothers brains change, how her research [00:03:00] fits into the reproductive rights debate in the United States, and whether the so called maternal instinct is a real thing.

[00:03:06] Section: Episode interview

[00:03:07] Monica Cardenas: alright, well thank you again, Chelsea. I'm so glad I get to speak to you about this book. I was thrilled when I saw it come out because it's something that I have been interested in for a long time. And the reason I asked Anna if I could speak to you about this book in particular was that some of my doctoral research is loosely connected to this idea of an inherent maternal instinct, whether it exists or not. And so I think the first question is what to you is mother brain? Where did this title of the book come from?

[00:03:44] Chelsea Conaboy: Yeah, so the title of the book really came from, I guess my own effort to try to understand what was happening to, to my brain after my first son was born in 2015. I felt really [00:04:00] overwhelmed with worry, and not only like worried about his wellbeing or breastfeeding or like my capacity to care for him, but also really like worried about the worry itself and feeling like it was a sign that something was kind of missing or broken in me, as far as like the certainty or overwhelming warmth that I had anticipated feeling in new motherhood.

[00:04:26] Chelsea Conaboy: And I'm a journalist and information is very much my way of coping with things. And so I went on a deep dive into the maternal brain research specifically and found there just a story that I felt like hadn't been told about the neurobiological changes that we go through as we make this really massive transition in our lives with profound hormonal changes, but also experiential changes and [00:05:00] lifestyle changes and our whole social context is changed.

[00:05:04] Chelsea Conaboy: So in 2018, I wrote a story for the Boston Globe Magazine about the maternal brain research specifically and my own experience with new motherhood. And that story really went viral. And I had already been thinking about writing a book, but then I realized like, oh, this thing that has been helpful to me can help a lot of other people too.

[00:05:27] Chelsea Conaboy: So I eventually got the book deal and the more I read about this research, the more I realized that it wasn't just a story for gestational parents. It really was a story for all parents. And so the book is called Mother Brain: How Neuroscience is Rewriting The Story of Parenthood. It's really a book in my mind for everyone who's doing this work or who cares about people who are doing this work of caregiving.

[00:05:52] Chelsea Conaboy: But we called it Mother Brain because so much of what I see as like the need [00:06:00] in our society is like really reframing what a mother is so that everyone, all parents can like benefit from this more generous narrative.

[00:06:11] Monica Cardenas: Yeah, I think it definitely accomplishes that. One of the first things I thought when I saw the title was, sort of a wink toward mommy brain or what people call mommy brain, which I think is usually insulting, used in insulting way that your memory isn't working as it should or you're forgetful. And is that something that you thought about? in

[00:06:36] Chelsea Conaboy: Absolutely. Yes. There was definitely like that element of like, no, this is like something of sophistication, I guess, like mommy brain is such a harmful trope in my mind that like, we are compromised by this time of life. And we can get into the details of that if you want. Like memory deficits are real, but they're also like one temporary and small [00:07:00] part of a much more complicated story about how we grow in this stage of life. And so yeah, definitely there was a wink towards like, this is not mommy brain, it's mother brain.

[00:07:10] Chelsea Conaboy: And also, you know, there's an element of that in just the cover design too. Like I really didn't want it to look like something that you would find in the baby aisle, you know? Um, because I wanted, I knew that people who were looking for that, that audience would find it anyway. And I wanted it to feel like this is a science book that says something to an audience that's much bigger than just expected parents.

[00:07:39] Monica Cardenas: Right, as you said, the subtitle is How Neuroscience is Rewriting the Story of Parenthood. So, what do you think the narrative was? How would you define the narrative before your research? How did we think about mothers and parenthood?

[00:07:56] Chelsea Conaboy: So I think there are many different ways that we think about mothers and parenthood, but [00:08:00] one really dominant. One in my mind is this idea of maternal instinct. I ended up really focusing on that because one of the questions that I asked with that original 2018 article that I wrote was, why aren't we talking about this more?

[00:08:16] Chelsea Conaboy: Like, why isn't this science already part of perinatal care? And in parenting books, and part of the conversation that we have with our care providers when we're pregnant during those many appointments, we go, we go to like, why isn't this conveyed to us?

[00:08:33] Chelsea Conaboy: And I think there's a couple of reasons for that. One is that the science is relatively new, although we know enough, in my mind, to start the conversation, obviously. But the other piece is that I think the science tells a really compelling story. The problem is we've had this other story. We've had this other story of maternal instinct that is so deeply ingrained in our society that it's hard [00:09:00] to get past.

[00:09:01] Chelsea Conaboy: And, I started looking at maternal instinct and it felt very like just something we take as fact. And the way I define it is, you know, this idea that the capacity for caregiving is innate and automatic and distinctly female.

[00:09:20] Chelsea Conaboy: And also that that idea is grounded in science. And so I started tracing that idea back and lots of feminist scholars have written about this in the past and so you know, I was able to look at their work and see that maternal instinct is not grounded in science. It's grounded in the moral and religious ideas of what a mother and a woman is that were really written into evolutionary theory and into instinct theory in the late 19th and early 20th century, and then carried forward and sort of repeated over and [00:10:00] over again and in new ways with each generation.

[00:10:04] Chelsea Conaboy: Until, in the book, I describe it as like a classic case of disinformation. It's something that has the plausibility of truth because we feel changed by parenthood and we see those changes in other people, and it just gets repeated again and again until we kind of believe it reflexively. So I think that's the story that I was kind of writing against in this book.

[00:10:28] Monica Cardenas: Yeah. And I think we see it repeated so much in culture. It's, it's everywhere you look, it's just taken for granted I think, until you start to pick it apart and it's true, I agree. I mean, based on my own research, feminist scholars have been saying this for generations, but I don't. Think there's a lot of scientific backing to some of those statements in the way that you've laid out in your book with scientific evidence [00:11:00] proving that men's and women's brains are different or women are just hardwired for it in that way. So can you talk maybe about what it is that you found that disproves this maternal instinct?

[00:11:14] Chelsea Conaboy: Yes. So, I guess starting with the idea that it's like innate or automatic, the science of the parental brain is really shows that there are two things that shape the parental brain. One of them is hormonal changes. You know, we talk a lot about the hormonal changes of pregnancy and how, how those hormones, allow a fetus to grow and initiate the progression of the pregnancy. And then labor and delivery and breastfeeding. We really don't talk very much, about what those hormones mean for the brain.

[00:11:45] Chelsea Conaboy: And what this research shows is that it's, they're kind of priming the brain to be really plastic or changeable, really highly moldable and ready essentially to receive the [00:12:00] stimuli that a baby provides. And the second thing that changes the brain is experience. It's really a matter of time and practice of caregiving. A couple of the researchers who I quote in the book talk a lot about how parenting is like ultimately a learning process. That's what this research shows.

[00:12:19] Chelsea Conaboy: It is something that is learned and it's learned at a time when our brain is really ready and like prepared to learn by the physiological changes we go through. So in that sense, like it isn't automatic, it is something that we develop. This is considered like, by some researchers, a distinct developmental stage for the brain.

[00:12:40] Chelsea Conaboy: It's not like there's this Lego piece that clicks on that is our like maternal instinct that, that like we just know what to do. It is something that we need. Practice in it is bi-directional, meaning it's shaped as much by our baby and their own genes and temperament and sense of agency as it [00:13:00] is by ourselves. And it's something that needs time to unfold. You know, it's a process.

[00:13:06] Monica Cardenas: I just wanna make sure I understand. So the hormonal changes help prepare your brain, get it ready to receive all this information and learn this entirely new job and lifestyle and everything that is different with having a child. What about, I know you spend a lot of time in the book explaining that this can apply to people who aren't actually birthing the child?

[00:13:36] Chelsea Conaboy: Yeah. Yes. So that's the next thing I was gonna say, this idea that like, this capacity for caregiving is inherently female or specific to gestational mothers. The science is also proving that to be untrue in the sense that overwhelmingly, the research that we have on the parental brain is in gestational mothers.

[00:13:57] Chelsea Conaboy: Um, because, the same narratives [00:14:00] that we have as a society get repeated over and over again in our science also. But that is beginning to change. There is a growing body of research and fathers. And to some degree, much smaller degree, but growing in adoptive and foster parents.

[00:14:15] Chelsea Conaboy: And what we see in them is that they also experience these same two factors, hormonal changes and experience. So fathers see shifts in their hormonal systems as they approach fatherhood and during early fatherhood, including changes in testosterone and prolactin, which we often think of as a milk making hormone, but it's really about bonding. And they experience similar spikes in oxytocin when they're interacting with their newborns that mothers do.

[00:14:46] Chelsea Conaboy: And there are changes both in function and structure over time in father's brains. And since my book has been published, there was a really significant study that came out that looked at the [00:15:00] MRI images of father's brains during their partner's pregnancies and then after their partner's pregnancy.

[00:15:06] Chelsea Conaboy: So in that shift from before their baby's born to after. And they found significant structural changes specifically across areas of the brain that are involved in social cognition or how we read and respond to another person's emotions and mental states, and that's very similar to what some of the same researchers have found in mothers, from before pregnancy to afterward, there are these shifts in social cognition.

[00:15:35] Chelsea Conaboy: So we're just finding that there are, you know, I wanna be careful here to say like, pregnancy is a very powerful force. You know, I, I am not saying that, gestational parents and other parents go through exactly the same changes. Like it's undeniable the intensity of pregnancy, but the mechanisms may be different, but for parents who are [00:16:00] very engaged and taking, like responsibility for their care of their children, the outcomes are quite similar kind of no matter how you get there.

[00:16:09] Monica Cardenas: I don't have children, but it seems to me that any parent who reads your book or understands the concepts here that you're describing, it would first of all probably relieve a lot of the pressure that a new parent would feel about just knowing what to do and hopefully be kinder to themselves as they're learning.

[00:16:32] Monica Cardenas: But also, give the father or an adoptive parent or parent who maybe didn't carry the child, a stake, an equal stake in the parenting and not feel sort of sidelined by not being the one who was pregnant.

[00:16:49] Chelsea Conaboy: I really hope that both of those things are true. So certainly, I think that that's what this research did for me, both me personally and in relationship with my husband,[00:17:00] was you know, it, I felt all that worry in new parenthood that I wasn't feeling things as I was supposed to be feeling.

[00:17:07] Chelsea Conaboy: And that that lack of like a specific kind of maternal emotion meant that I was a bad mother and already, you know, from the start. And in reality, this is a process that unfolds differently from individual to individual and takes time. And you know, we didn't talk about this yet, but, the changes that happen in gestational parents in the early months are really directed towards driving our attention towards our children and some of the changes, overlap a lot with anxiety and worry.

[00:17:45] Chelsea Conaboy: And so I was able to look at the science and say I'm not broken. I need support. But also things are happening just as they should in, in many ways that I am going through this process of change that's gonna shape me into the parent that [00:18:00] my child needs me to be. And so I hope that that message does give people a lot of like patience and grace for themselves to just get the support they need and also go easy on themselves and their expectations.

[00:18:13] Chelsea Conaboy: And then also, yes, absolutely. I think there's a lot of pressure for mothers to do it all and also a lot of unhelpful social narratives around the role of fathers and other parents in those early months. This idea that like, well, babies only need their mothers, and so, you know, there's just not, like, not much we can do. And that's just not true. Babies can connect with other loving, attentive caregivers. And not only that, but that connection is really important for those parents themselves because they need the exposure to their babies, just like the gestational parent does in order to do the work of learning how to understand their cues and their mental states.

[00:18:57] Chelsea Conaboy: You know, babies are these tiny, [00:19:00] vulnerable nonverbal creatures who depend on us to know what their needs are, even when we don't yet always have the language to understand, understand what those needs are, and it, you learn them by practicing and making mistakes and trying again. And fathers and other parents, you know, they need that time to learn as well.

[00:19:22] Chelsea Conaboy: And this is a big message I think in relation to parental leave and the need for all parents to have time with their new newborns because they need that exposure to have kind of the healthiest possible transition to parenthood that they can.

[00:19:39] Monica Cardenas: You wrote an op-ed in the New York Times, when your book was published, about how maternal instinct is a myth that men created and how that myth has been perpetuated. And we talked a little bit about that. How is what we have historically called maternal instinct [00:20:00] different from what you're describing, right, because it seems to me that maternal instinct has been applied just a blanket instinct for all women, whether they have children or not. They just know how to take care..

[00:20:15] Chelsea Conaboy: Yep. Yep. Yeah. I mean, I think an innate understanding of how to take care of one another is different than a process by which you learn how to do it. You learn it by doing and by making mistakes and by struggling through it, you know, that is fundamentally different.

[00:20:33] Chelsea Conaboy: I think the early writers of instinct theory and who included maternal instinct, you know, one of them was William McDougall, an early psychologist. And he wrote that like parental love was strongest in women and could overcome all other instincts, even fear itself.

[00:20:54] Chelsea Conaboy: And then he went on to write that it wasn't stronger however, than a woman's [00:21:00] education, that that maternal instinct declined as women were more educated. And so in order to preserve maternal instinct, which for McDougall was closely connected to preserving white supremacy because it was white women, he wanted to be having more babies, preserving maternal instinct in his mind required social sanctions, like laws against divorce or, institutions that would discourage divorce and birth control and women's education.

[00:21:31] Chelsea Conaboy: And, thereby keep them having babies. So, I mean, this was not a subtle thing, you know, this is not like feminist scholars have not had to reach very far to see that this was a, a construct that was used to keep them in a certain place, which is at home.

[00:21:52] Monica Cardenas: You talked a little bit already about how actual scientific research was also, how it has [00:22:00] historically marginalized women. So how, I guess the approach to that research has treated women differently or has been based on the assumption that women's brains are completely different to men's brains, and how culturally, mothers have been quote cherished and sort of put on this pedestal.

[00:22:22] Monica Cardenas: So I think we can see how that categorization has hurt women and, you know, built these narratives over time, but can you explain a little bit more about that history? How women that were marginalized in science and then also the culture?

[00:22:38] Chelsea Conaboy: I mean, so women were marginalized in science and they still are in many ways. So, I guess I'll go back to the, a group of women called, referred to often as Darwinian feminists. These were women, like I write in the book about Antoinette Brown Blackwell, who wrote one of the first feminist critique of the theory of [00:23:00] evolution in the late 19th century.

[00:23:02] Chelsea Conaboy: And, she really, the narratives about what a woman was prior to that were were shaped in, her world anyways, by the Bible. And so here was a theory that broke down the wall between humans and animals and sort of freed women potentially of this like evil temptress narrative.

[00:23:22] Chelsea Conaboy: And she believed that women were gonna take this and use it, that they were gonna look at the questions that were sort of the center of their lives and use science to answer them. But what happened was that women were largely walled off from science as a professional institution, that they weren't admitted to the institutions that were training people in science or to the professional organizations.

[00:23:47] Chelsea Conaboy: They were sidelined, essentially. And as science became a professionalized field broadly, they were not admitted. And so over time that changed, you know, generations later, women [00:24:00] started to, you know, more women started to become scientists, and I write in the book about a group of anthropologists in the late sixties and seventies who, women who were kind of among the first women in their field, anthropologists, evolutionary biologists studying primates and how people like Sarah Blaffer Hrdy and others kind of went out and did field work and realized that the narratives that they'd been told about, like what primate motherhood looked like and relationships looked like didn't match what they were seeing in the field.

[00:24:40] Chelsea Conaboy: And so they started looking at all that through a different lens and came up with these very different ideas of what a mother's behavior is in different species. And not sure if I'm answering your question directly enough, but my point is really that like women in science changed science[00:25:00] and that is still like a really evolving story.

[00:25:04] Chelsea Conaboy: You know, you mentioned the excerpt that ran in the New York Times, I got a lot of response to that. And a lot of it was from angry men and, and some women on the internet. And some of it was from scientists, particularly I would say like conservative leaning scientists who embrace the idea that men and women's brains are really fundamentally different.

[00:25:32] Chelsea Conaboy: One of them in particular wrote a long essay that, in response to mine, that got shared by other scientists and passed around quite a bit. And you know, one of the arguments was that like you can see maternal instincts across other animal species, and we are animals.

[00:25:50] Chelsea Conaboy: Like kind of the message of like, have you ever seen a mama bear protecting her cub? And the problem with that argument is like, I'm not [00:26:00] arguing that she's not protective and that that's not real, that like compulsion to care for her baby is not real. It is. I felt it myself also as a new mother. It is really a fundamental piece of that experience of new parenthood.

[00:26:15] Chelsea Conaboy: It's just, I don't think we get there by just this flip of a switch. And also there's lots of different models of parenting all across the animal kingdom and all across mammalian species. Parenting looks different from species to species. Caregiving is like an evolutionary lever essentially that changes according to a species social niche.

[00:26:43] Chelsea Conaboy: And there are some primates in which the mothers do all of the caregiving and don't ever put their babies down until they fend for themselves, essentially. And there are other primates in which there's a community of animals who care for the child. And our social [00:27:00] niche has developed such a way that we are a hyper social species and we are that way, partly because we have had babies in very close succession.

[00:27:11] Chelsea Conaboy: That's a thing that like distinguished us from other primates. And in order to do that, we needed help. Like babies couldn't be cared for only by their one mother. They needed other adults to support them. And so our caregiving brains developed with that in mind. That was a very long answer. But like, I just, I guess my point is we have gotten to that story in large part by women being part of science and asking questions in the context of their own lives.

[00:27:44] Monica Cardenas: Right. And that's something we need across the board, not just in science, right, but to balance the voices and the perspectives in all parts of the world, right? Not just science and medicine, but [00:28:00] politics and the law.

[00:28:01] Chelsea Conaboy: Absolutely. I mean, I think that's a huge message that women in science have changed science, and that's also what we need in politics and in policy making and in how decisions are made in our community in healthcare. Healthcare is a big one, like in terms of not only those people who are doing the caregiving, but also those who are deciding how money is spent and where those resources should go.

[00:28:28] Monica Cardenas: Speaking of politics, so when it comes to reproductive rights in the US and restrictions on abortion access, one of the arguments that we often hear, and we did hear from Amy Coney Barrett in the Dobbs decision was essentially that if a woman doesn't want to continue a pregnancy, she should just have the baby and give it up for adoption.

[00:28:56] Monica Cardenas: Does your research, inform any part of that, do you [00:29:00] think? Or would you reject that based on anything that you found in your research?

[00:29:05] Chelsea Conaboy: I would reject that. I mean, I think that there is this biological essentialism that runs through that idea that, well, you can just have the baby and give it up, that your body was just made to do that. And so that's like a simple concept. Like just you, you have the baby and, and you pass it on.

[00:29:25] Chelsea Conaboy: And it's, it, I'm laughing at the absurdity. It's not actually funny. But the thing that I think stretches beyond reproductive rights, but is certainly at the center of it, is this idea that women can do this and simply have the baby and pass it on, is grounded in this idea that like, our bodies are made to do this and so we can, and that like willfully ignores the fact that pregnancy is incredibly costly.

[00:29:56] Chelsea Conaboy: And I mean that from a biological sense that it is [00:30:00] an incredible burden for our bodies in terms of the resources that we have to give to it. Our stress system, this is something that is really underappreciated, I think, in our understanding of pregnancy, that our stress systems are absolutely pushed to the max during pregnancy.

[00:30:20] Chelsea Conaboy: And that is in a normal, in a normal pregnancy, your hormones. We haven't talked about hormones, sort of like settling out and returning to normal after like a period of baby blues, but your hormonal system has changed forever. It never actually goes back exactly to what it was.

[00:30:36] Chelsea Conaboy: So I think that that idea that Amy Co, that really the Dobb's decision as a whole embraced ignores the fact that we are changed by pregnancy and the early postpartum period and we are changed physically and mentally, and that is not a short term reality. We often think of [00:31:00] pregnancy as like an event, like something with a beginning and an end. And that's in how we deal with it in the law and socially and culturally. And, also in healthcare. You know, once the baby arrives really your amounts of healthcare for the mother or the gestational parent falls off a cliff in the United States in particular. And so we see it as this sort of contained event, when it's actually like this really powerful developmental stage that changes you for the rest of your life.

[00:31:30] Monica Cardenas: Can you give us some examples of how those changes stay with you forever?

[00:31:36] Chelsea Conaboy: I mean, there are like the obvious ones that people are kind of more aware of in terms of like your physical body, and especially if you have any kind of complications during pregnancy, like if you have preeclampsia or more serious complications, traumatic childbirth, you have a c-section, like those are kind of the most obvious physical things that you can have [00:32:00] complications from over the rest of your life.

[00:32:03] Chelsea Conaboy: But also something that I think is underappreciated is the reality of traumatic childbirth childbirth and how many people experience P T S D as a result of that. Postpartum depression and anxiety. Many people experience their first ever bout with depression during , the postpartum period. And those who do are then more likely to experience depression later in life as well.

[00:32:30] Chelsea Conaboy: So there are these like physical and mental risks that are increased for the long term as a result of pregnancy. But there are also like a lot of things that we don't understand yet because we haven't studied them. There's a really fascinating researcher in Australia who is studying how anxiety is essentially is processed in the brain[00:33:00] after a pregnancy, meaning well after a pregnancy. She's actually studying fear specifically and how we develop fears and then extinguish fears.

[00:33:10] Chelsea Conaboy: And essentially the, the mechanisms for extinguishing our fears are changed by pregnancy and seem to be changed permanently. Her work is in rodents, but there's some research that she's doing in humans also. And there are like some basic brain functions that seem to be changed by pregnancy that we, that, over the long haul that we still don't fully understand.

[00:33:34] Chelsea Conaboy: And there is really fascinating research that looks at cognitive changes over the long term in mothers specifically and you know, having babies and particularly having a lot of babies raises your risk of Alzheimer's quite significantly.

[00:33:51] Chelsea Conaboy: But there's some research trying to figure out why that is. And it seems like it probably is an [00:34:00] interaction between pregnancy and particular gene variants. And so if you have one of those variants, then having a lot of babies increases your risk. And if you don't, then it's not as significant.

[00:34:11] Chelsea Conaboy: And that's sort of one example of like a bunch of things that we have to answer about how pregnancy affects your health over the long term. One researcher described this to me as like kind of a, a last frontier of understanding disparities by sex and gender in long-term health that we really haven't looked much at reproductive history as a factor in someone's long-term health. It's missing from like a lot, a lot of studies. And so, what we know is that it is a major factor and we don't really know exactly how.

[00:34:49] Monica Cardenas: Interesting.

[00:34:50] Chelsea Conaboy: Yeah.

[00:34:50] Monica Cardenas: Going back to the, the first example you gave about processing fear , a change in how you process fear, that seems [00:35:00] to me like something that would really fundamentally probably change your perspective on a lot of things if you have to completely re-engineer...

[00:35:10] Chelsea Conaboy: Yeah.

[00:35:11] Monica Cardenas: ...how you respond to something. So common,

[00:35:14] Chelsea Conaboy: Yeah, I mean, I think I'm like a little bit reluctant to talk in depth about that research, partly because it's very early and like she hasn't, her name is Bronwyn Graham. She hasn't like fully published those results. But she talked with me about some of them. But at like an anecdotal level, I think that's something that would ring true for a lot of people who have had a baby.

[00:35:37] Chelsea Conaboy: We know there are changes in prevalence of anxiety and o c d and other kind of manifestations of worry, bipolar disorder as well. And then just that like kind of a nonclinical level, I think mothers often say, many have told me like I can't watch scary movies anymore, or, you know, the news affects me really differently than it used to.

[00:35:59] Chelsea Conaboy: So [00:36:00] I do think whether we like point to like a specific brain circuit that changes, that has that result or not, I talk a lot in the book about how these broader changes in the brain cause this like shift in worldview and how you relate to things that are happening around you and to other people. And so I think that is real.

[00:36:24] Monica Cardenas: Okay.

[00:36:25] Chelsea Conaboy: Yeah.

[00:36:25] Monica Cardenas: I'll move on a little bit from the history..

[00:36:29] Chelsea Conaboy: I just wanna something that is so cool that just in talking about how having a pregnancy affects your body over the long term. Something else that I really love to talk about is pregnancy results in something called microchimerism, which is when fetal cells cross the placenta into the parent's body, not just like pieces of DNA but actual cells and essentially like take up residence in the body.

[00:36:57] Chelsea Conaboy: And, their function is like a little [00:37:00] bit unknown still, that it seems like they may be beneficial in some ways. They're found at often at like the site of c-section scars or other wounds that they may have a role in healing and directing resources towards the injury, for the body to recover from it.

[00:37:19] Chelsea Conaboy: But there's also some indication that, that they may also result in some cost to the gestational parent that they're appear often in like mammary tissue, so there might be like directing resources towards milk production. But they've been found also in the brain and one study looked at the brains of a range of women and found these fetal cells and one woman as old as 94. So they seem to stay in the body and so I think this is really like elegant example of there is no like end point to a pregnancy in terms of how it affects us over the long haul.

[00:37:58] Chelsea Conaboy: Like these [00:38:00] pieces of our pregnancy, of the fetus remain in us forever. And it's something we don't understand yet, but it seems to have, you know, real consequences, good and potentially in conflict with our own bodies, you know, over the long haul. And there's still so much that we don't know.

[00:38:20] Monica Cardenas: Those changes, I think one of the first examples you give in the book, one of the real life examples, is a woman who thought that she wanted to go back to work soon after she had her baby, sooner than she was offered maternity leave, I guess. But after she had her child, she wasn't sure she wanted to go back at all.

[00:38:44] Monica Cardenas: Based on the research you've done, would you put that down to the initial anxiety and worry she had about her child and I guess her presence reassuring herself that everything was okay, or was [00:39:00] that maybe part of the longer term change where her focus changed? Or would she return to her career eventually? Or find that as interesting later when she got past the postpartum period?

[00:39:15] Chelsea Conaboy: It's an interesting question. I, I'm, her name was Emily, and I'm trying to think of how she would answer that.

[00:39:22] Chelsea Conaboy: I can probably better answer that question from my perspective. I, because in some ways her story and mine were similar in, in that like, early worry. So I felt that intense like worry and protection, sense of protection in the early postpartum period. And there is research that has found that these circuits that are really highly active in those early postpartum months that are really focused on directing our attention towards our baby, these are areas of the brain that are involved in motivation and meaning making and vigilance. So I think of them as like the things that like help us to keep our babies [00:40:00] alive to like really stay focused on meeting their needs and also push us into this really intense period of learning.

[00:40:06] Chelsea Conaboy: 'cause you're so closely focused on them that you can't help really, but like learn their cues and what they need. And there's a sense in the research that that high activity shifts over time around possibly three to four months, essentially as your social cognition the networks that are involved in social cognition are changed, that activity becomes like more balanced. Basically you get better at reading their cues and at making the mistakes that you have to, and shifting your behavior as a result, that process of becomes a little bit easier or you're more finely tuned. And so there's like a drop in that hypervigilance activity.

[00:40:47] Chelsea Conaboy: I can see that in my own experience that my own kind of like cocooning eased a little bit over time. I describe it in the book as kind of a little bit of exposure therapy. Like you [00:41:00] take your baby out into the world and you realize that like they're okay. You also get help from other people and you realize that that's okay, like you kind of just do it slowly and you realize it's possible.

[00:41:13] Chelsea Conaboy: I do feel like, I guess maybe because of that change in social cognition, there is like a certain kind of reprioritizing things. Like I can't ever put my kids aside, you know, it's entirely to focus on something else. They are always gonna be in my mind, or at least it's hard to do that. It's hard to ever close that piece off. So I think that speaks to some of these long-term changes.

[00:41:45] Chelsea Conaboy: I talk in the book about these brain networks that are involved in our sense of ourselves are changed, the systems that take the cues coming from our own bodies and what's happening in the world around us [00:42:00] and create these like narratives about who we are and what we need, and that we use to like predict our own needs in the future.

[00:42:08] Chelsea Conaboy: Those networks are changed, and one researcher described it to me as like, it's possible that they are sort of extended to now include our children as well, so that there is like Yeah, there is like an extension of the self in a way uh, it has like some neurobiological grounding.

[00:42:32] Monica Cardenas: Wow. And I'd imagine that that intense period of learning the baby's cues as you were describing and that hypervigilance you said...

[00:42:41] Chelsea Conaboy: Yes. Yeah. Yep.

[00:42:42] Monica Cardenas: ...takes up everything. Right? I can imagine that it takes up all of the, your brain's capacity, right? So it would make sense then that you can't imagine trying to squeeze in.

[00:42:55] Chelsea Conaboy: Yes. I mean, it, it's really fascinating. There's some great research in rodents [00:43:00] that really shows this very clearly that there are some rodent, uh, rodents who were essentially raised to be dependent on cocaine. Then when they become mothers, they're like set up into these tasks where they can choose between the cocaine and their pups and they choose the pups. So it's like pups are just this really powerful stimuli. This really power, you know, that's hard to deny.

[00:43:27] Monica Cardenas: Oh, that's fascinating. So, we don't have a lot of time left, but I want to ask now you've explained what the past narrative was and how it marginalized women and what the science tells us now. What would you like the new narrative of parenthood to be and how that take

[00:43:51] Chelsea Conaboy: I Yeah. Would

[00:43:54] Monica Cardenas: Or do you see evidence of that happening?

[00:43:56] Chelsea Conaboy: Yeah

[00:43:57] Monica Cardenas: that take

[00:43:57] Chelsea Conaboy: I would like [00:44:00] to see new parenthood really embraced as a developmental stage of life. And if we fully do that, I think it requires us to some major changes in our healthcare system, in our social policies, and also in how we talk to one another about what it means to become a parent.

[00:44:22] Chelsea Conaboy: I like to look toward like the teenage brain science, that body of research is a little bit farther ahead than the parental brain science. And it's been used in really interesting ways. It's been used, here in the United States for example, to change school start times because there's a recognition now that the teenage brain needs more sleep, and happens on like a different circadian rhythm.

[00:44:44] Chelsea Conaboy: It's been used in some places to change disciplinary practices in schools and to change how we deliver like public health messages to teenagers around substance use and other risky behaviors. And it's also [00:45:00] been used, it's like been taken to parents themselves to say, here's what's happening with your teenager and here's what that might mean for your relationship and how you raise them. And this is what's happening in their brains, like understand them better.

[00:45:15] Chelsea Conaboy: And similarly, it's been given to teenagers to say like this is an important moment for your mental health. This is what's happening in your brain and here's how you can help yourself. And I feel like a very similar conversation needs to happen with the parental brain research, to take it to the policy makers and the institutions that impacts young families', health and wellbeing to say like, we need to start thinking about this.

[00:45:41] Chelsea Conaboy: And we need to give it to people who work with new parents and who are new parents to, to say like, this is what's happening in your brain and here's the support that you likely will need and how to get it. And here's how you can help yourself.

[00:45:56] Monica Cardenas: Yeah, and there's a relief in that I think, because [00:46:00] if you, as you described in the book, if you were, are just thinking about it, really insularly or you imagine that it's only you that feels this way, there's such a loneliness and fear I think in that. So with just the knowledge that it's a universal experience or as you a developmental stage,

[00:46:21] Monica Cardenas: right? That, that

[00:46:22] Chelsea Conaboy: I think, um, a lot of people experience

[00:46:25] Monica Cardenas: it

[00:46:25] Chelsea Conaboy: Feeling blindsided Yeah. I think, a lot of people express feeling blindsided by the change in themselves and their inner lives in new parenthood. And I, I really do think the science can help us avoid some of that by giving people the language that they need to understand what they're going through when it happens.

[00:46:49] Monica Cardenas: And on that subject, one of the things that I really loved about your book is that it is scientific, but still totally accessible. I feel [00:47:00] like anybody can understand it the way you've explained these things. So are there other books, that you think tackled this subject or similar subjects in the same way, in the same accessible way.

[00:47:13] Chelsea Conaboy: Yes. This is like the first book that kind of really dives deep into the parental brain research for like a lay audience, I would say. But, there are one, of the researchers, who I quote a lot in the book and who was really important for shaping this book, her name is Jody Poluski, and she has a book that she's written in French that is about to come out in an eng English language version. It's called Mommy Brain. I love her and I agree with her on a lot. We like differ a little bit about the use of that phrase. But I have read parts of that book and it's also very worthwhile and written from the perspective of someone who's done this research and is also a clinician.

[00:47:56] Chelsea Conaboy: I would also say there are two books that I [00:48:00] love about the history of motherhood and culture and science. One is called The Nature and Nurture of Love by Marga Vicedo. She's a historian, a medical historian. And the other is called From Eve to Evolution by Kimberly Hamlin. Those are different in that they're really like looking at the history of the science, more than what's current. But they're really interesting.

[00:48:25] Monica Cardenas: Right.

[00:48:26] Monica Cardenas: Lastly, I wanted to ask a question about The Feminine Mystique by Betty Friedan. Anna and I recorded an episode about that that will be out later this season, and during it we talked about the idea that women would be entirely fulfilled by being housewives, taking care of their husbands and children all day, which is what Ferdinand covers in the book. I'd like to ask you what you think the "new" feminine mystique might be. If your research shows that a mother's brain is changing and life is evolving dramatically, then it makes sense that they might be consumed by life as a mother. [00:49:00] And it sounds like maybe this previous idea of the feminine mystique from the 50s and 60s was somehow extended to apply to all women, all the time, rather than a specific developmental stage that you talk about in your book. What do you think?

[00:49:17] Chelsea Conaboy: I mean, so I, I hear you and I feel like this is a little bit tricky in, in the nuance, but also like an important part of the conversation

[00:49:25] Chelsea Conaboy: So I hear you and I feel like this is a little bit tricky in, in the nuance, but also like an important part of the conversation that doesn't actually come up in interviews a lot. So thanks for asking about it. That like early stage is really intense and I think it is undeniable that like our focus is pulled to our children. It's necessary.

[00:49:46] Chelsea Conaboy: And it eases over time. And I think it can be true, both things can be true, that like we are fundamentally changed by having kids and we [00:50:00] still wanna be humans out in the world, right? Like, just because we are changed by them doesn't mean that our whole focus is them.

[00:50:07] Chelsea Conaboy: And that we will be completely fulfilled by that role. And, that is like so grounded in gender, essentialism, you know, and these old ideas of what a mother is. And like maternal instinct I think has this piece attached to it that it, it is an instinct that overcomes all else.

[00:50:25] Chelsea Conaboy: So that we will be fulfilled in that role when in reality these brain changes happen in the context of the brains we already have. Like this is a growth of who we are to begin with, and who we are changes, but doesn't, like, it's not subsumed by the parental brain. We grow with the brains we already have, which includes, you know, our interests and our, and our strengths and also our challenges. You know, all the capacities we have come with us.

[00:50:55] Chelsea Conaboy: And that is true. And also [00:51:00] I think we develop, we can develop, in a way that even brings us into new capacities. There's some research that, is only like a very small handful of studies, that that looks at how our brains respond to or even interact with other adult brains after we've had babies. And this has been, in particular like in relationship to partners or to other caregivers, like how we relate to other caregivers may change.

[00:51:35] Chelsea Conaboy: And a part of the book where I really kind of very transparently like extrapolate from that because this is not grounded in science yet, but like, I kind of imagine what those findings could mean is like, what if that role as caregiver becomes like a construct for how we see the world around us.

[00:51:55] Chelsea Conaboy: And so now we relate to other parents in a new way. [00:52:00] Our social cognition or our empathy anyways for other people changes, our like desires for how we wanna interact in our communities change, and maybe even grow or extend beyond our family unit in new ways. So I just, I think this idea of like the angel of the house has so limited our understanding of what a parent can be, and the science really opens us up to like a lot of new possibilities.

[00:52:28] Monica Cardenas: Right. Thank you Chelsea. That was fascinating and I really appreciate you taking the time to talk more about your book.

[00:52:37] Section: Outro

[00:52:38] Anna Stoecklein: Thanks for listening. The Story of Woman is a one woman operation run by me, Anna Stoecklein. So if you enjoy listening and want to help me on this mission of adding woman's perspective to mankind's story, be sure to share with a friend. One mention goes a long way. Hit that subscribe button so you never miss an episode and make sure to rate and review the podcast while [00:53:00] you're there.

[00:53:01] Anna Stoecklein: For more content from the episodes and a look behind the scenes, follow The Story of Woman on your social media platforms. And for access to bonus content, ad free listening, or to have your personal message read at the end of every episode, consider becoming a patron of the podcast. Or you can buy me a one time metaphorical coffee. All of this goes directly into production costs and helps me continue to put out more and better episodes. In exchange, you'll receive my eternal gratitude and a good night's sleep knowing you're helping to finally change the story of mankind to the story of humankind.

💌 Sharing is caring